Cavendish Mews is a smart set of flats in Mayfair where flapper and modern woman, the Honourable Lettice Chetwynd has set up home after coming of age and gaining her allowance. To supplement her already generous allowance, and to break away from dependence upon her family, Lettice has established herself as a society interior designer, so her flat is decorated with a mixture of elegant antique Georgian pieces and modern Art Deco furnishings, using it as a showroom for what she can offer to her well heeled clients.

Lettice is far from Cavendish Mews, back in Wiltshire where she is staying at Glynes, the grand Georgian family seat of the Chetwynds, and the home of Lettice’s parents, the presiding Viscount and Countess of Wrexham and the heir, their eldest son Leslie and his wife Arabella. Today she is being entertained by a neighbour, of sorts, of her parents, Mr. Alisdair Gifford, nephew of Sir John Nettleford-Hughes and his Australian wife Adelina at their Wiltshire home of Arkwright Bury, a Regency style country house, partially overgrown with creepers, set amidst a simple English park style garden, which was destroyed to some degree in a fire in the 1870s, but was then restored. During the ensuing years, when the house passed from Mr. Gifford’s father to Mr. Gifford’s older brother, Cuthbert, the house fell into disrepair. When he committed suicide after the war, the house was inherited by Alisdair Gifford, as Cuthbert had no spouse or offspring. The present Mr. and Mrs. Gifford have spent the better part of the last five years trying to save and restore Arkwright Bury from the ravages of neglect.

Mr. Gifford’s uncle, Sir John Nettleford-Hughes was the one who set the wheels in motion for Lettice to visit Arkwright Bury and his nephew, Mr. Gifford. Old enough to be her father, wealthy Sir John is still a bachelor, and according to London society gossip intends to remain so, so that he might continue to enjoy his dalliances with a string of pretty chorus girls of Lettice’s age and younger. As an eligible man in a time when such men are a rare commodity, with a vast family estate in Bedfordshire, houses in Mayfair, Belgravia and Pimlico and Fontengil Park in Wiltshire, quite close to the Glynes estate, Lettice’s mother, Lady Sadie, invited him as a potential suitor to her 1922 Hunt Ball, which she used as a marriage market for Lettice. Luckily Selwyn Spencely, the handsome eldest son of the Duke of Walmsford, rescued Lettice from the horror of having to entertain him, and Sir John left the ball early in a disgruntled mood with a much younger partygoer. Lettice recently reacquainted herself with Sir John at an amusing Friday to Monday long weekend party held by Sir John and Lady Gladys Caxton at their Scottish country estate, Gossington, a baronial Art and Crafts castle near the hamlet of Kershopefoot in Cumberland. To her surprise, Lettice found Sir John’s company rather enjoyable. As she was leaving to return to London on the Monday, Sir John approached her and asked if she might meet with his nephew, Mr. Gifford, as he wishes to have a room in his Wiltshire house redecorated as a surprise for Adelina, who collects blue and white porcelain but as of yet has no place to display it at Arkwright Bury. Lettice arranged a discreet meeting with Mr. Gifford at Cavendish Mews to discuss matters with him, and now has come to luncheon with the Giffords at Arkwright Bury under the ruse that she, as an acquaintance of the Giffords with her interest in interior design, has come for a tour of the house.

“So that is the end of the restored part of the house, Miss Chetywnd. I do hope you enjoyed the tour.”

“Oh I did, Mr. Gifford.” Lettice enthuses. Turning to his wife she continues, “Mrs. Gifford, as an interior designer, I have an intimate knowledge of what it takes to restore a room, and I must say you’ve done splendidly with your interiors.”

“Thank you Miss Chetwynd,” Mrs. Gifford, a slight woman with translucent skin and dark hair arranged in a soft chignon, answers, her cheeks colouring with a blush. “That’s a great compliment coming from you. I suppose I know what Arkwright Bury looked like, thanks to Alisdair’s father’s photographic collection of the interiors,” She sighs. “And I know what I like, so I had a very definite vision.”

“We still have a few rooms left to go.” Mr. Gifford says. “But just lately, we both seem to have run out of energy.

“Five years of restoration can do that to a person, I would imagine.” Lettice remarks.

“There are more than a few rooms, Alisdair,” his wife chides him kindly, calling out his optimism as being false as she folds her arms akimbo and gives her husband a hopeless look. “Be fair.”

“Oh, very well, Adelina. I concede. There may be a few more than a few rooms still to be restored and renovated, but at least we have completed about three quarters of the restoration. Thank goodness! Shall we continue?”

“Do you really want to see the unrestored rooms, Miss Chetwynd?” Mrs. Gifford asks. “They are very shabby looking, and in some cases are practically box rooms we use for storage of items that are yet to be placed around the house.”

“Oh yes, Mrs. Gifford.” Lettice replies enthusiastically. “I’m very interested to see what you have had to deal with upon inheriting Arkwright Bury.”

“Oh very well. Lead on Alisdair.” she replies.

The trio walk down a corridor that shows the signs of ingrained dirt and dust and possibly a leak in the roof at some stage, judging my the smell of damp that now pervades the air.

“It must have been in quite a state, when you inherited it from your brother, Mr. Gifford.” Lettice remarks, looking at a ragged piece of William Morris wallpaper hanging from the wall to her right.

“Oh it was frightfully run down.” Mr. Gifford opines, as you can see. He stops and fingers the edge of the lose wallpaper. “Terrible really. I don’t know what Cuthbert paid that caretaker pair for, but they did nothing, or the bare minimum whilst he was away at war, and I can’t say they did a great deal more once he came back, judging by the state of the roof when we inherited this pile of stones.” Mr. Gifford sighs heavily. “Not that poor Cuthbert would have noticed what they did once he came back from the front. Ahh, here we are.” He remarks as they approach a small Maplewood door. “My brother’s study.” Mr. Gifford gives the door a shove with his shoulder, causing it to creak and groan as it opens. “Damp in this part of the house caused all the doors to warp.” he says as a form of explanation. “Please do excuse the mess, Miss Chetwynd.”

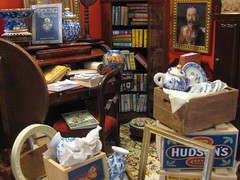

Lettice and Mrs. Gifford follow Mr. Gifford through the door and Lettice looks around her. The room is small, and appears smaller because of the oppressive red wall hangings and the ramshackle collection of objects and furnishings stuffed into every conceivable space in any way possible, in spite of light pouring in through two windows. Tables and stools sit atop other tables. Tottering stacks of boxes balance precariously, some of them sending forth a tumble of aging tissue paper or old newspaper, wrapped around plates, pots and vases, all of blue and white painted porcelain. The room was evidently used as a study at some stage, with the space dominated by an old Victorian mahogany rolltop desk, the top pulled back, the surface barely discernible beneath piles of papers.

Noticing Lettice’s gaze fall upon the papers, Mr. Gifford explains, “My brother wasn’t well when he came back from the war.” He reaches into an open chocolate box that is stuffed with yellowing and fading pieces of paper: invoices, correspondence and empty envelopes all jumbled up with notes written by Cuthbert scrawled on scraps of paper. “Goodness knows what it all means. It doesn’t make any sense to us, but it must have to him.”

“The haunt of a troubled and haunted soul.” adds Mrs. Gifford as she picks up a dusty periodical about art from 1912 and then tosses it onto the dusty velvet seat of the chair drawn up to the desk, the action eliciting a cloud of tumbling dust motes from the cushion.

“King George!” Lettice remarks with astonishment, pointing to the portrait of the King in a gilded frame hanging up on the wall next to the Georgian corner cabinet she now recognises from the photo of the Pagoda Room, stuffed full with a jumble of books.

“Oh yes,” Mr. Gifford replies. “Apparently Cuthbert found the King’s gaze somewhat of a comfort to him in those last months of his life, so he replaced the portrait of our father that now hangs in the entrance hall, with this print of the King.”

“I can’t say I’d find the King gazing at me as I sat working at my desk, very restful.” Lettice admits with an awkward chuckle. “The exact same portrait hangs in the Glynes village hall. My siblings and I always felt sorry for whomever was manning the second-hand clothing stall at the village fête each year as children. No-one wanted to be under His Majesty’s piercing gaze.”

“I agree, Miss Chetwynd.” Mrs. Gifford adds. “It is quite piercing.”

“As I said, Cuthbert was not in his right mind when he returned from the war,” Mr. Gifford tries to explain. “So goodness knows what he saw that the rest of us plainly don’t.”

Lettice looks around at the stacks of old, musty books, the salvaged pieces of furniture that must be destined for elsewhere in the house, and the worn and sun faded oriental rug beneath their feet. “This must be your collection of blue and white china you were talking about before, Mrs. Gifford.” Lettice remarks, trying to draw the attention away from the ghost of Mr. Gifford’s dead brother.

“Yes, it is.” Mrs. Gifford replies absentmindedly as she reaches into a box with an apples label on it and pulls out a bulbous Chinese vase decorated with a blue vine leaf pattern. “I’m going to turn this room into a place where I can display my collection,” She sighs as she replaces the vase back into the box. “Eventually.”

“When we have the vim and vigour again.” Mr. Gifford adds.

“Yes,” his wife agrees laconically.

“Well, I’m happy to give you some advice, if you like Mrs. Gifford.” Lettice offers gently.

“Oh that’s kind of you, Miss Chetwynd, but I think I’ll just throw up a few shelves around the walls in here.” Mrs. Gifford replies brusquely, waving her hands about the dust mote spattered air around her. “That will do.”

“Adelina!” Mr. Gifford exclaims. “Miss Chetwynd was only trying to help.”

Mrs. Gifford pauses and looks guiltily at Lettice, who cannot hide the offence she took from the woman’s gruff rebuttal of her. “Oh, I’m sorry, Miss Chetwynd!” she exclaims, putting her palms up in defence of herself. “I didn’t mean for my words to come out like that. I mean no disrespect.”

“Its quite alright, Mrs. Gifford.” Lettice replies breezily, trying to fob off the snub. “Really it is.”

“I should just like to explain that I don’t want you to get your hopes up.” Mrs. Gifford clarifies.

“My hopes, Mrs. Gifford?”

“I don’t know what Sir John told you, but restoring Arkwright Bury has been no mean feat, and was far more costly than we imagined it would be when Alisdair inherited it and we took the old place on.” Mrs. Gifford goes on. “We hadn’t been here since before the war, probably summer 1913, wouldn’t you say, Alasdair?”

Mr. Gifford puts his finger and thumb to his clean shaven chin in contemplation as his lids lower over his hazel eyes. “Probably Adelina, or maybe autumn, but 1913 definitely. When Cuthbert came home from the war, he became a recluse, so we didn’t visit him here, and therefore hadn’t seen how the rot set in until after the funeral.”

Mrs. Gifford looks Lettice squarely in the face. “I know you are an interior designer, but I think your style is far too grand for modest little Arkwright Bury, hidden here in provincial Wiltshire.”

When Mr. Gifford visited Lettice in London, she had agreed that if she took him as a client and redecorated the room for him, that it would be kept a secret from his wife so that it would be a surprise for her, so Lettice keeps up the ruse, even though she hasn’t yet agreed to accepting Mr. Gifford’s commission. “Well, my advice comes at no charge, Mrs. Gifford, I assure you. I’m only here because I am visiting my parents and was able to pay a call on you, at the behest of your husband’s uncle, who suggested I might be of some assistance to you when I met him at the Caxtons’ country house party a few weeks ago.”

“And we really would be grateful for any advice, Miss Chetwynd, wouldn’t we Adelina?” He looks seriously at his wife, his eyes growing wide with unspoken words as they silently implore her to be polite to Lettice. “As you said, Adelina, work on restoring Arkwright Bury has taken its toll on both of us, including our ability to think creatively. This project has just absorbed our every waking moment, Miss Chetwynd.”

“Alisdair is right, Miss Chetwynd. I’m sorry. I suggested putting up some shelves because it really is simply the easiest solution to displaying my collection, but if you have other ideas, I’d certainly take them under advisement.” Mrs. Gifford replies with both weariness and wariness in her voice. “However, I think Alisdair and I have done a splendid job of restoring the old girl.” She pats the wall next to her. “And I’ve put my mark on her.”

“Oh, and you have, Mrs. Gifford, splendidly!” Lettice exclaims. “No, I am only here because Sir John suggested that I may be able to be of assistance. I’m not touting for business from you, unwarranted.” She smiles, glad to tell the truth that she did not seek out this appointment, but was rather sought out instead, even if she selectively and conveniently leaves that fact out of her statement. “And I’ve recently taken on a commission for Sir John and Lady Caxton.”

“Well it was very good of you to come and visit, Miss Chetwynd.” Mrs. Gifford replies with evident relief in her voice. “Although we aren’t quite neighbours, your parents’ paths do cross with our own at county functions.”

“Thus why we were at your parent’s Hunt Ball those few years ago, when we first had the pleasure of making your acquaintance, Miss Chetwynd.” Mr. Gifford pipes up cheerfully.

“Now, if you’ll excuse me, Miss Chetwynd, I must go and see about luncheon. At least I managed to retain my cook from Briar Priory, so I don’t have to break her in, unlike some of the housemaids I have on staff.” Mrs. Gifford casts her eyes to the heavens. “I keep having to remind them which side to serve from when Alisdair and I dine at home, which is frightfully embarrassing for all concerned when we have guests: so consider yourself pre-warned, Miss Chetwynd.”

“Noted, Mrs. Gifford.” Lettice replies.

As Mrs. Gifford opens the door of the study, which protests noisily upon its hinges as she does, she turns back. “And I’m supposed to be the colloquial little colonial.” She beams a cheeky smile. “Oh, thinking of which, you are in luck today, Miss Chetwynd.”

“How so, Mrs. Gifford?”

“We took possession of a crate of wines from my father’s South Australian vineyard this week, so we will be having antipodean Verdelho with our fish course this afternoon. I shall leave you in the capable hands of my husband to finish the tour, Miss Chetwynd.” Mrs. Gifford looks to her husband. “I’ll see you both in the dining room, promptly at one, Alisdair.” She nods and eyes her husband seriously.

“Adelina knows I have the propensity to chat and forget all about the time.” Mr. Gifford admits guiltily.

“And Mrs. Grimsby’s schedule.” Mrs. Gifford adds. “And I certainly don’t want her to take umbrage and give notice, Alisdair. I don’t want to have to break in a new cook as well.”

“I promise Adelina, dear.” Mr. Gifford replies.

“Good show, Alisdair!” his wife pipes as she turns on her heel. “I’ll see you both there shortly.”

Lettice and Mr. Gifford both chuckle like naughty children as the door closes and the sound of Mrs. Gifford’s footsteps retreat down the corridor outside.

“I can see that rather determined streak we seem to encounter in most Australians,” Lettice remarks. “However she’s not at all what I expected, Mr. Gifford.”

“What were you expecting of my wife, Miss Chetwynd?” Mr. Gifford queries.

“Oh,” Lettice sighs as she shrugs her shoulders. “I suppose I was expecting a woman a little more forthright in her speech.”

“Oh Adelina can be very forthright when she feels that she’s been wronged, or she perceives her opinion isn’t being given much heed, Miss Chetwynd. You heard her say before that she appreciates your opinions, but she has her own plans for this room.”

“Yes, I did notice those less than subtle statements.” Lettice raises an expertly plucked eyebrow. “Which makes me a little uneasy, Mr. Gifford.”

“Uneasy, Miss Chetwynd?”

“Yes. I mean I feel as though your wife has some definite ideas for this room in order for it to house her collection of blue and white porcelain.”

“Like get our carpenter to throw up a few shelves along the walls in here after giving the room a fresh lick of paint?”

“Well, even though it perhaps isn’t what I would do, yes, Mr. Gifford, it is still her collection.”

“But that’s exactly why I want your help, Miss Chetwynd. Adelina is a wonderful woman, and she’s done so much to help with restoration of Arkwright Bury, and put up with so much inconvenience in the process, but her interior design ideas are very unimaginative. When we lived at Briar Priory, her collection was housed in a little room we called the China Room. It was a dressing room I think, or maybe even a small study in the Eighteenth Century, and it was converted into a cabinet for the display of curios and porcelain in the Nineteenth Century, so it was perfect. It was so much more than what Adelina is proposing for in here.”

“Pardon me for asking, Mr. Gifford, but won’t your wife take offense if I do agree to take this room on an redecorate it?”

“Why would she take offense, Miss Chetwynd.”

“Well, for a start, she will have no input into the room’s decoration, Mr. Gifford.”

“Well of course she won’t, Miss Chetwynd. As I think I explained to you in London, I want this to be a marvellous surprise for her, when we come back from our little seaside holiday to Bournemouth: a reward for all that she has done for the rest of Arkwright Bury.”

“And it is that very ‘all the rest’ that concerns me. From our tour of the house, I can see how much Mrs. Gifford has been involved in the restoration, redecoration and transformation of your home. If I were her, and some impudent woman from London came along and put her own stamp upon the house…”

“You’re hardly impudent, Miss Chetwynd.” laughs Mr. Gifford.

“Be that as it may, Mrs. Gifford may not perceive it that way.”

“I promise, Miss Chetwynd, that if you take Arkwright Bury on, and Adelina doesn’t like what you do, I will take full responsibility and incur any wrath from her. After all, this was all my idea.” Mr. Gifford assures Lettice. “However, I’m sure you will once again be surprised by my wife. You yourself admitted that when we first met you as the new owners of Arkwright Bury at your parent’s Hunt Ball two years ago, and you found out that Adelina was Australian, you were surprised.”

“Expecting a woman from Australia to have burnished skin and sun bleached hair, rather than pale, almost translucent skin and raven black hair is hardly the same as what her feelings are, Mr. Gifford. Emotions are emotions, no matter who we are, and I don’t wish to upset your wife.”

“You won’t, Miss Chetwynd.” Mr. Gifford insists. “I assure you. I’ve been married to Adelina for six years now. We were married just after Armistice Day**, and I knew her as a nurse during the war, so I know Adelina far better than you do.”

“Oh, I don’t doubt it, Mr. Gifford,” Lettice agrees. “But I find that decorating a house, especially one that is to become one’s home, is very personal. I wouldn’t want someone going behind my back, even with the best of intentions. I’d resent it as a gesture.”

“She won’t resent you, Miss Chetwynd.”

“Perhaps.” Lettice mutters non-committally.

“Now, what is it that you would do, Miss Chetwynd?”

“Me, Mr. Gifford?”

“Well of course. I’m not employing you, not to have an opinion, you know.”

“You are presumptuous, Mr. Gifford. I still haven’t said that I will take you on as a client, yet.”

“Yet, but you will.” he replies with self-assurance.

“If Jeffrey and Company*** agree to produce a small quantity of wall hangings of my sketch, based upon what used to hang in here, I’ll agree, Mr. Gifford.” Lettice clarifies. “However, they have not agreed yet. They have taken my sketch of the pattern under advisement and will consider my request once I go back to the with measurements, which you will give me before I leave Arkwright Bury today, Mr. Gifford.”

“So, you said you wouldn’t just install shelves like Adelina is suggesting, Miss Chetwynd. What would you do?”

Lettice looks around the cluttered and dusty room, and tries to imagine the space without the old roll top desk, the stacks of papers and boxes, the excess furniture and the crates of Mrs. Gifford’s blue and white porcelain.

“Well, I certainly wouldn’t cover the walls in shelves. They will only make this room smaller and darker.” She looks around her again, squinting as she tries to envision what the space could look like. “This room gets the morning light, doesn’t it?” Lettice asks as she points to one of the large sash window, partially obscured by a stack of boxes and a folded Chinese screen leaning against its frame. When Mr. Gifford nods in confirmation, she goes on, “I’d paper the walls in the design I’m trying to get Jeffrey and Company to reproduce, or failing that, some equivalent orientally inspired paper with a white background to compliment the china.” Lettice pauses.

“And then?” Mr. Gifford breathes as he encourages Lettice to go on.

“Well, I’d keep this.” She taps the side of the worn Georgian mahogany corner cabinet, running her fingers lovingly along the rope pattern trim that indicates where the fretwork covered glass door sits when it is closed. “But then again, I am a firm believer in preserving pieces of a house’s history, and if this survived the conflagration of, 1879, then I think it deserves to remain.”

“Oh I agree, Miss Chetwynd. No matter what happens to this room, the Georgian corner cabinet stays.”

“Is this destined for elsewhere in the house, Mr. Gifford?” Lettice asks, as she walks around Cuthbert’s open rolltop desk littered with its piles of fading and yellowing old papers gathering dust and a ginger jar missing its lid, which she realises may be the one pictured on an ornate pedestal in the photograph of the Pagoda Room at Arkwright Bury taken in 1876, that she has in her possession at Cavendish Mews. She wraps her fingers around the rounded edge of the tilted top of a loo table**** and squeezes it.

“We had that in the entrance hall of Briar Priory for all the newspapers and the mail. Adelina had a large green majolica jardinière in its centre with an fishbone fern in it, however the table already in the entrance hall here actually suits it far better than that loo table would, and would be too hard to try and remove the existing table downstairs anyway. So in short, no, Miss Chetwynd.”

“Then I would put this in the centre of the room and display either some larger objects, like that tazza*****,” She points to the blue and white footed shallow bowl standing atop a small footstool standing indignantly on the top of Cuthbert’s desk. “Or a few favourite pieces of Mrs. Gifford’s on it. What are your wife’s favourite pieces in her collection, Mr. Gifford?”

“Well, there is a rather lovely hexagonal Chinese teapot around here somewhere.” Mr. Gifford replies, looking distractedly around him. “Oh, and this.” He carefully picks up a willow pattern teapot with a gilded spout and lid from a box spewing forth a stack of blue and white plates in various sizes and frothy yellowing tissue paper. “It’s Eighteenth Century and apparently quite rare: not that a philistine like me would know. Her father bought it from a curios shop in Adelaide and brought it over for Adelina’s birthday a few years ago. It’s her pride and joy.”

“Well, then a few curated pieces from the collection on the table.”

“And the rest, Miss Chetwynd?” Mr. Gifford looks around him at the stacks of boxes.

“A couple of carefully selected small Georgian breakfronted bookcases****** should house the majority of the pieces I can see, and be amply able to display Mrs. Gifford’s collection well, even if she continues to acquire some new additions. Perhaps a couple of small wine tables******* and a few pedestals for some other select or larger pieces. Your wife could even hang a few of the charger plates******* on the wall, if suitably positioned. It would leave the room, which is really quite small, appearing much more spacious than it is, due to a lack of furniture, and the white background of the patterned wallpaper would make the room lighter and take advantage of the morning sunlight.”

“Well, I’m sold, Miss Chetwynd.” Mr. Gifford sighs as he claps his hands. “When may I commission your adroit services?”

“I haven’t said yes yet, Mr. Gifford.” Lettice tempers him again.

“But I can see the brightness of excitement in your eyes, Miss Chetwynd. You can’t deny it.”

“I’m considering it, Mr. Gifford.” Lettice admits warily, knowing that Mr. Gifford’s observant eye has caught her out. “But I will not commit to it, yet.”

“Yet…” Mr. Gifford replies with a satisfied sigh.

Lettice is just about to try and curtail Mr. Gifford’s enthusiasm again when a loud metallic clang from the clocktower built over Arkwright Bury’s nearby stables announce the hour. The chime of the clock marking the hour heralds the flutter of birds’ wings as the doves that nest around the roofs of the country house fly out into the air in a startled fashion.

“Good heavens! Is that the clock!” Mr. Gifford exclaims, quickly putting the teapot back into the open box stacked atop several others. He fishes out his silver pocket watch from his breast pocket of his vest. “It’s one o’clock already, and Adelina will be expecting us for luncheon. Come along, Miss Chetwynd.”

Mr. Gifford puts an arm around his guest protectively as he guides her out through the door and into the corridor, closing it behind him, leaving the deserted study to fall into sullen silence once more, as dust motes raised by its recent visitors cascade through the air.

*Antipodean means relating to Australia or New Zealand (used by inhabitants of the northern hemisphere), such as “antipodean wines”.

**Armistice Day or Remembrance Day is a memorial day observed in Commonwealth member states since the end of the First World War to honour armed forces members who have died in the line of duty. It falls on the 11th of November every year. Remembrance Day is marked at eleven o’clock (the time that the armistice was declared) with a minute’s silence to honour the fallen. Following a tradition inaugurated by King George V in 1919, the day is also marked by war remembrances in many non-Commonwealth countries.

***Jeffrey and Company was an English producer of fine wallpapers that operated between 1836 and the mid 1930s. Based at 64 Essex Road in London, the firm worked with a variety of designers who were active in the aesthetic and arts and crafts movements, such as E.W. Godwin, William Morris, and Walter Crane. Jeffrey and Company’s success is often credited to Metford Warner, who became the company’s chief proprietor in 1871. Under his direction the firm became one of the most lucrative and influential wallpaper manufacturers in Europe. The company clarified that wallpaper should not be reserved for use solely in mansions, but should be available for rooms in the homes of the emerging upper-middle class.

****A loo table, also known as a tip-top table, is a folding table with the tabletop hinged so it can be placed into a vertical position when not used to save space. It is also called a tip table and a snap table with some variations known as tea table or pie crust tilt-top table. These multi-purpose tables were historically used for playing games, drinking tea or spirits, reading and writing, and sewing. The tables were popular among both elite and middle-class households in Britain and America in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries. They became collector's items in the early in the Twentieth Century.

*****A tazza is a shallow cup or vase on a pedestal. First used in Britain in 1824, it comes from the Italian for cup, as well as derivations in Arabic and Persian dialects.

******Breakfront refers to any piece of furniture (especially a bookcase or cabinet) that has a central section that projects farther forward than the other sections.

*******A wine table is a late Fifteenth Century device for facilitating after dinner drinking, the cabinetmakers called it a "Gentleman's Social Table." It was always narrow and of semicircular or horseshoe form, and the guests sat round the outer circumference. The wine table might be drawn up to the fire in cold weather without inconvenience from the heat.

********A charger plate is a large, decorative plate that acts as a base for other dinnerware. Also known as service plates, under plates, or chop plates, charger plates are purely ornamental and aren't intended for direct food contact. Charger plates serve both aesthetic and practical purposes. Visually, charger plates provide elegance and enhance table decor. Practically, they protect the table and tablecloth from becoming dirty during service and help retain heat in dinnerware.

This rather untidy room, unloved and cluttered with items, including some you may recognise from the photo Mr. Gifford showed Lettice of the original Pagoda Room, may look real to you, but it is in fact made up of pieces from my 1:12 miniatures collection, including items from my childhood.

Fun things to look for include:

Cuthbert’s mahogany rolltop desk is a miniature that I have had since I was about eleven years old. The top does roll up and down, and the pigeon holes and writing area of the desk move forward, just like a real rolltop desk. I bought the desk along with a lot of other 1:12 miniatures from a High Street speciality dollhouse shop in England. The receipt with a few handwritten amendments is actually the scroll with the pinked edge in the far right pigeon hole of the desk! The balloon backed chair with the buttoned velvet seat before it I have had since the age of seven.

The corner cabinet I acquired from Kathleen Knight’s Dolls House Shop in the United Kingdom. The pedestal table and embroidered footstool standing upside down atop the desk also comes from there, as does the embroidered footstool on the ground and the grandfather clock to the right of the photograph. The round loo table standing to the left of the photograph tilts like a real loo table and is in its upright position, showing its underside. It is an artisan miniature from an unknown maker with a marquetry inlaid top, and also came from Kathleen Knight’s Dolls House Shop in the United Kingdom.

The books in the corner cabinet and on top of the desk are 1:12 size miniatures made by the British miniature artisan Ken Blythe. Most of the books I own that he has made may be opened to reveal authentic printed interiors. In some cases, you can even read the words, depending upon the size of the print! I have quite a large representation of Ken Blythe’s work in my collection, but so little of his real artistry is seen because the books that he specialised in making are usually closed, sitting on shelves or closed on desks and table surfaces. The magazine sitting on the chair and the boxes of papers on the desk’s pull-out writing space are also Ken Blythe’s work. What might amaze you even more is that all Ken Blythe’s books and magazines are authentically replicated 1:12 scale miniatures of real volumes. To create something so authentic to the original in such detail and so clearly, really does make this a miniature artisan piece. Ken Blythe’s work is highly sought after by miniaturists around the world today and command high prices at auction for such tiny pieces, particularly now that he is no longer alive. I was fortunate enough to acquire pieces from Ken Blythe prior to his death about four years ago, as well as through his estate via his daughter and son-in-law. His legacy will live on with me and in my photography which I hope will please his daughter.

The hand painted oriental ginger jar on the pedestal in the background next to the corner cabinet I acquired from Melody Jane’s Doll House Suppliers in the United Kingdom.

Adelina’s blue and white china collection, spewing from the boxes and gracing the top of the desk, are all sourced from a number of miniature stockists through E-Bay, but mostly from Kathleen Knight’s Doll’s House Shop in the United Kingdom.

The wooden boxes with their Edwardian advertising labels have been purposely aged and came from The Dolls’ House Supplier in the United Kingdom.

The Portrait of King George V in the gilt frame in the background was created by me using a portrait of him done just before the Great War of 1914 – 1918.